With increased urbanisation, rural chinese farm workers are having to adjust to life outside of their traditional commune lifestyle. With the development of the Chinese middle-class, more and more families are relocating and altering their way of life, which has left many members of the older generation struggling to adapt.

Collective Living in Rural China

When the Communist Party of China (CPC) came into power between 1921 and 1949, its main goals was to improve the lives of the average Chinese citizen. Since most citizens at the time lived in rural areas, the CPC took great efforts to transform rural life in key areas. This was mainly due to the introduction of collective living, whereby control of land was appropriated by the state from traditional landowners.

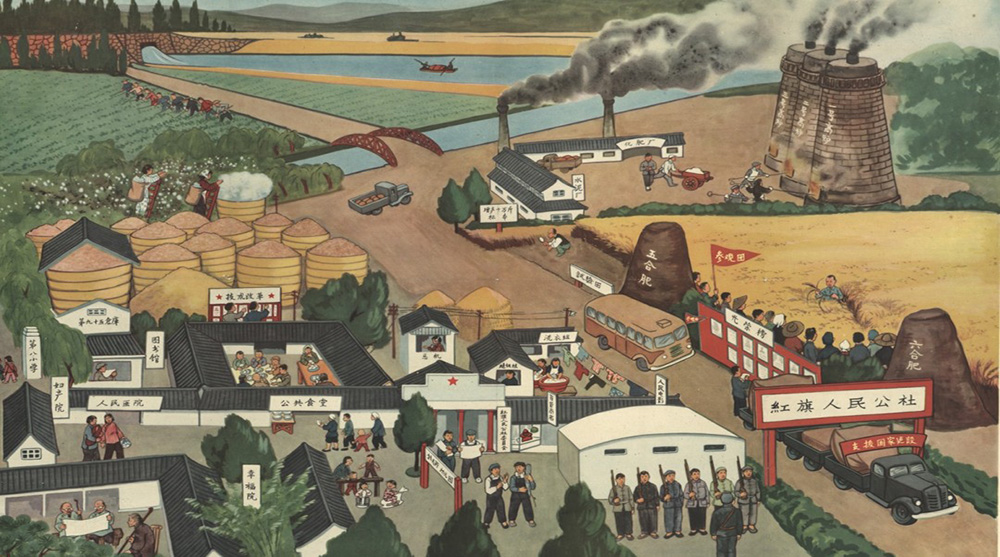

Collectivization of rural China

Collectivization of agriculture began in 1955, and by the following year 96% of all farming households had been absorbed into cooperatives. This system was supplanted by the commune system in 1958, in which the government redistributed the land as well as the resources in order to create a more fair system of agriculture and industry in rural China. During the process, village elites were ousted and replaced with new village leaders who showed support for the movement.

The redistribution took place on a massive scale, with cooperatives of thousands of members from up to 100 villages each being merged into communes. Approximately 20 to 30 cooperatives were merged into a single commune during collectivization, each comprising of over 20,000 members from 40 to 100 villages.

By 1959, almost all Chinese farm workers were members of communes, each overseen by an economic and administrative unit that controlled the labour force and all means of production from central management of industry and commerce, as well as education and military affairs. Any land, equipment, or cash still held by the peasants all became the property of the commune.

Communal living

As the name suggests, communal living in rural China meant that workers had shared resources and worked as part of a centrally-controlled unit. Workers would perform industrial and agricultural tasks in order to farm their assigned areas, and they would utilise shared facilities such as communal nurseries, bathing facilities, barber shops, etc. Every aspect of the operation was controlled by the state, including wages and prerequisites, and everything was marketed through state-controlled agencies.

Within the commune system, the household was the basic unit of consumption, and the standard of living was fairly uniform throughout rural territories. However, there was little chance for any upward mobility of workers unless they banded together to form a ‘commune cadre’ or obtained a scarce technical position such as a truck driver.

The inefficiency of large collectives proved to be the downfall of Chinese communes. They were decentralised in the early 1960s, with some being divided into private farms, and in the 1970s individual households were given the opportunity to purchase long-term leases for their farms. A fixed amount of their production was then paid to the state and the farmers could consume or sell the rest. Farmers were now allowed to sublet their land, recover capital investments, hire additional labour, own machinery, and make agricultural decisions.

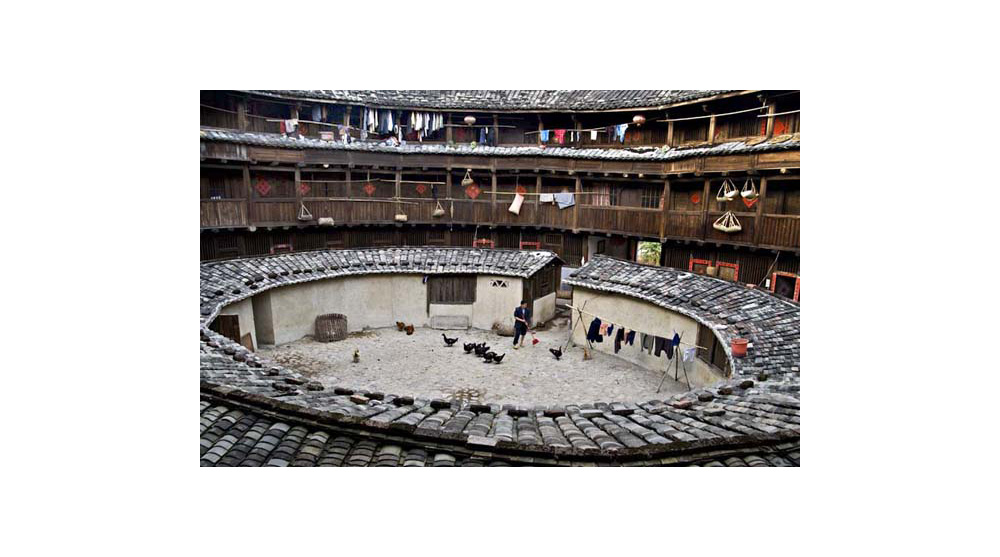

The disappearance of communal lifestyle

With several generations all living under one roof, individualism was discouraged and privacy was never expected. Friends would wash together, students share crowded dormitories, and children were encouraged to put the needs of the group first and their own second.

With the emergence of the middle class, individuals were able to afford to buy their own homes and personal space, as well as their own transport and overseas travel away from the rest of the family. With more money circulating this new middle class, new aspirations, and even new values, are emerging.

China's new middle class is not just buying houses and cars, it is buying a new lifestyle. In old China, communal living and communal values went hand-in-hand. But now many Chinese aspire to their own space and a new culture of individualism may be emerging.

Top 3 Reasons Why You Should Enter Architecture Competitions

Curious about the value of architecture competitions? Discover the transformative power they can have on your career - from igniting creativity and turning designs into reality, to gaining international recognition.

Learn more